24 oct. 2018 By Stephan Jaeggi

In the early 1990s, Desktop Publishing (DTP) technology had superseded the proprietary typesetting and image processing systems of the eighties. Because of the relatively low investment and the ease-of-use of the new technology, a new division of work became possible. Ad agencies, graphic designers and even print customers started to create print layouts on their own. Eventually these pages needed to be transferred to the print shop. At the beginning, imaging service bureaus which imaged the pages on film were quite popular. But with the advent of ComputerToPlate(CtP) the print shops could not process film anymore, they required digital data.

At that time there were two methods to transfer print layouts from a designer to a print shop: via PostScript file or sending the original layout files. PostScript was not very suitable because of its device dependency. The results were not predictable and no method to control PS files was widely available. That’s why most users sent their native layout files to their printers. But this was quite error prone. Layout applications don’t save all data in one layout file but use links to external files (images, illustrations) and also require the installation of the same fonts at the reception end. Another problem was that the final result was often dependent on the version of the layout application, the installed plug-ins/extensions and even the operating system. This made transfer of layout data quite challenging.

That’s why I was very pleased when at the Seybold conference in San Jose in 1991 Adobe announced a new data format called Interchange PostScript (IPS) which promised to overcome the limitations of PostScript. It looked like the transfer problem would be solved eventually. But when PDF and Acrobat 1.0 were released in 1993 the deception among the users in print production was great because PDF 1.0 only supported RGB colors. No CMYK nor spot colors were possible. Therefore, PDF 1.0 could only be used for b&w documents. PDF 1.1 didn’t bring any improvement in 1994. With PDF 1.2, it was eventually possible in 1996 to define PDFs for printing since this version allowed CMYK and spot colors.

However, some objects which are often used in high end printing (e.g. duplex images, spot color gradients) were still not possible with PDF 1.2. On the initiative of Olaf Drümmer, CEO of callas software, an expert group from Germany and Switzerland had created a white paper in 1998 which described a series of shortcomings and limitations (e.g. no bleed), workflow problems (e.g. fonts) and desirable functionality (e.g. color separations) which at that time were the reasons that PDF could not be used as universal data format for all prepress data. This white paper got a lot of positive feedback from the industry and some vendors were encouraged to develop solutions for the topics mentioned in the white paper. In 1999, PDF 1.3 and Acrobat 4.0 as well as some plug-ins from third parties (Lantana CrackerJack, callas pdfOutput Pro, Quite A Box of Tricks) solved many of the issues.

At the end of the century, PDF became more and more popular for the digital exchange of prepress data. The first PDF output workflows systems were introduced by the traditional manufactures of CTP systems (e.g. Agfa, Creo, Heidelberg) allowing to benefit from the advantages of PDF in preparing the data for output (color conversion, trapping, imposition, etc.). The RIPs in front of the plate setters however were still based on PostScript. The PDF flats had to be converted to PostScript before imaging the plates.

PDF 1.3 was the base for the first PDF/X standards by the ISO in 2001 and 2002. PDF/X-1a was limited to CMYK and spot colors while PDF/X-3 also allowed ICCbased colors. However, the PDF/X standards only define the minimal technical requirements for digital prepress data. Intentionally quality criteria, which vary depending on the print product and the printing technology were not part of the ISO standards. The Ghent (PDF) Workgroup (GWG) founded in 2002 took over this task by defining PDF/X-Plus specifications. These PDF/X-Plus specifications are the base for the well-known recipes, settings and preflight profiles of PDFX-ready Switzerland starting in 2005.

Since the PDF format, creation tools as well as output workflows and RIPs have evolved over the years, the ISO standard PDF/X-4:2008 was released in 2008. The main new feature was live transparency. In 2010 the standard was slightly adapted and released as PDF/X-4:2010.

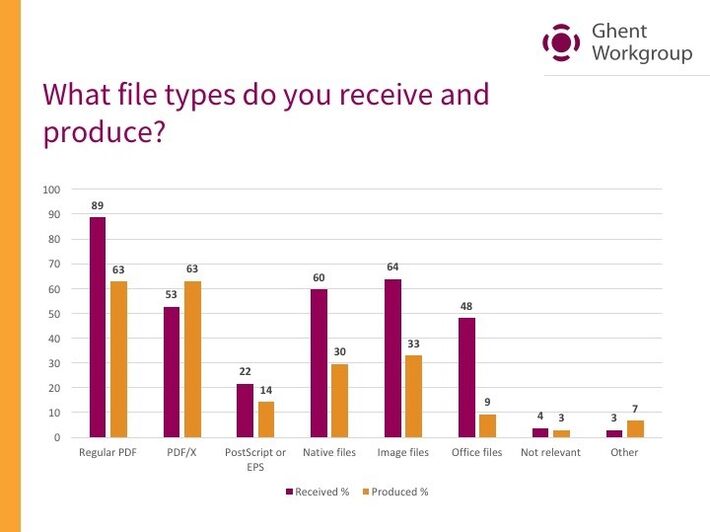

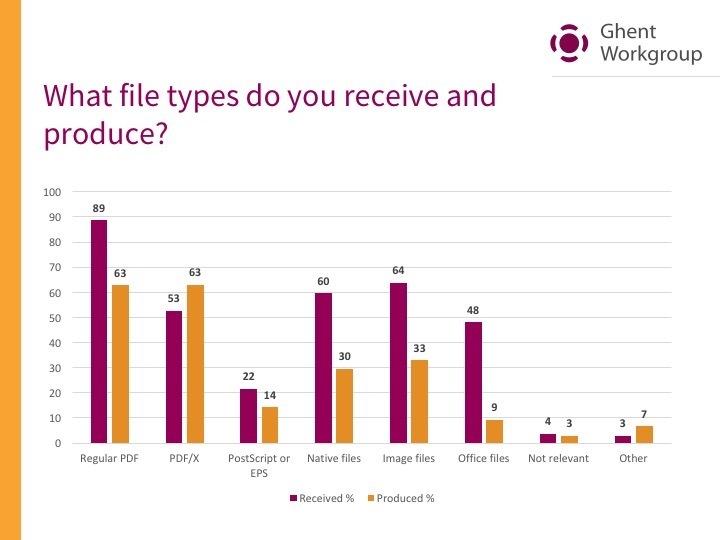

In the last 15 years PDF became the most important format for the exchange of prepress data. A recent survey of the Ghent Workgroup revealed that PDF and PDF/X were the most used file formats:

In a more detailed survey on PDF-AKTUELL about the popularity of the different PDF and PDF/X versions, PDF/X-4 was the most used format.

In July 2008 the ISO-Standard 32000-1 was released. It was based on PDF 1.7 which was issued by Adobe in November 2006. Intentionally there were no new features in ISO 32000-1. New features were only added in the first revision completely done under the control of the ISO. After nine years of work ISO 32000-2 (better known as PDF 2.0) was published in July 2017.

Currently our ISO working group is preparing the release of PDF/X-6 which is based on PDF 2.0 and is expected to be published in 2019…

- StephanJaeggi, PrePress-Consulting, Switzerland, publisher of PDF-AKTUELL

Nous utilisons des cookies pour suivre l'utilisation et les préférences. Pour en savoir plus, consultez notre page sur les cookies.